home

|

Appearances & News

|

||

|

2025

Library

Workshop

Series

Triskel Arts Centre Cork

Waterford

Parnell Square, Dublin

and Enda Wyley

Culture Night with other poets & Musicians

August

22nd to 26th August

18th to 20th June

10th June

9th

Readings

& Appearances 2022 November

3rd to 5th

Readings & Appearances 2021 August

24th August

25th Readings & Appearances 2020 January

26th Readings & Appearances 2018 Sunday September 30th Readings & Appearances 2017 October 6th -11th Thursday April 27th

Readings & Appearances 2016

September 16th

July 15th to 18th Velestovo Poetry Nights, Lake Ohrd, Macedonia

Readings & Appearances 2015 April 24th

Readings & Appearances 2014 August 16th &17th July 25th Reading at Waterstones Booksellers, Cork January 19th

Readings & Appearances 2013 November 16th November 14th Cafe U Dvoritsu, Zagreb, reading from Poezija

November 12th

November 7th Keats-Shelley Memorial Association, St Martins-in-the-Fields, London, where I gratefully received the 2013 Keats-Shelley Prize for Poetry November 3rd

October 30th

May

Participating in 2013 Spring Festival « Le Banquet du Livre », in Lagrasse, South of France.

April 18th Crossroads Festival, Bookshop West Portal San Francisco 7pm

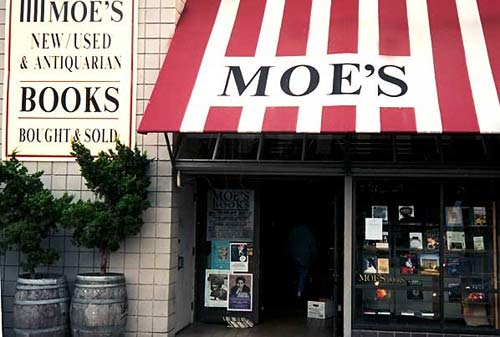

April 16th Poetry Flash, at Moe's Books, Berkeley 7.30pm

April 13th Poets West, Green Lake Branch Seattle Public Library 4pm

April 11th Poetry Foundation, Chicago, recording podcast

April 9th

Readings & Appearances 2011 November 3rd Reading at Cork City Library to mark launch of New Anthology celebrating SIMON Friday October 7th Lunchtime reading at the Irish Writers' Centre, Dublin August 24th -29th Struga Poetry Evenings Festival, Macedonia August 19th-20th Velestova Poetry Nights Macedonia Saturday February 19th

Readings & Appearances 2010 Saturday October 9th at The Liberties 998 Guerrero, San Francisco. Tuesday October 5th Moe's Books, Berkeley, California. Article about this event in Eastbay Express

Friday September 17th The Short Story & New Media - A

Seminar Frank O'Connor International Short Story Festival, Cork Thursday August 26th City Library Galway for Over the Edge May With James Harpur, Irish Pavilion at Shanghai Expo

Readings & Appearances 2009 March 10th 10.00am Handan campus, Fudan University, Lecture Room 217 of No.5 classroom building, College of Foreign Languages and Literature March 12th 14.00 Shanghai Normal Univeristy East Campus, Room 106, Foreign Language Department March 14th 12.00 Reading at the Shanghai Literary Festival, Glamour Bar, Bund 5 March 29th Reading at The Poetry Now Festival Dun Laoghaire April 7th 7pm Launch of new book Making Music at Cork City Central Library April 21st - 25th Reading at the International Istanbul – Beyoğlu Poetry Festival May 31st - June 5th Introducing Irish authors at the European Short Story Festival Zagreb, Croatia. September 16th - 20th Curating the Frank O'Connor Interanational Short Story Festival in Cork. details here.

Readings 2008

June 6th, 7th and 8th Reading at Force 12 Literary Festival in Belmullet, Co. Mayo. September 13th and 14th Reading at the Full Moon Poetry Festival (Täiskuu luulefestival) in Rapla, Estonia. October 15th - 19th Reading at the Cuisle Poetry Festival in Limerick. Wednesday 8pm Belltable Arts Centre November Reading at the Unitarian Church, Stephen's Green, Dublin on thursday 6th at 6.30pm November 21st Reading at the New Sorbonne, Paris. December 15th Featured Poet at O Bheal, Long Valley, Cork.

Why Munster Poets? A paper delivered to open the symposium on Contemporary Munster Poetry in English on Friday May 23rd 2008 When I preface my remarks by saying that this is not an academic paper but a polemic. I’m not making an apology. I’ll begin with a quote: “It seems that every writer has to make the imaginative grasp at identity for himself and if he can find no means in his inheritance to suit him he will have to start from scratch.” The exclusivity of male pronouns in that statement is indicative of the age in which it was made and of its author: Thomas Kinsella in Sean Lucy’s “Irish Poets in English” published in 1972. Kinsella’s male preference was further expressed in 1986 when his Oxford Book of Irish Verse was published containing no living Irish poet of the female gender. But it was an exclusion of more than gender. It excluded a great many other poets too, most neatly by its date of birth cut off point, poets who not only failed to fit in by age but who also failed to suit Kinsella’s programmatic agenda, mainly because their work was influenced by traditions other than the one Kinsella was promulgating. In 1985 in John Haffenden’s book of interviews with contemporary poets, Kinsella was asked: “Do you feel a kinship with other contemporary poets?” Kinsella responded: “The simple answer is: No. I don’t feel that there is a group activity afoot in which I play a part, or a creative heave in which maybe two or three poets are engaged. I don’t think it’s as coherent as it looks: it would be pure journalism to think like that.” I can’t help thinking that that is the answer to a different question from the one which Haffenden asked. I believe it’s possible for a poet to share a kinship with another without having to belong to a movement or group linked by written or unwritten manifestoes. I will expand on this point later when I focus on Munster poets. We all recognise in Kinsella’s response here the genesis for the infamous locution ‘journalistic entity’. I don’t think I’m being overly cynical when I see a huge irony behind the contradiction of Kinsella’s various statements and actions. I wholeheartedly agree with his declared sentiment that a poet must start from scratch in the formation of his or her identity, where identity is a synonym for voice; and even where identity might be some atavistic code word for national belonging I still agree with the idea that if one can find no means in one’s inheritance to suit, one must begin from scratch. But in promulgating the exclusive idea of his dual tradition and shaping it by that notorious anthology Kinsella effectively would deny to an Irish poet any option of starting from scratch. Patrick Galvin, Padraig Fiacc, Desmond O’Grady, Michael Longley, Maire Mhac an tSaoi, Eavan Boland and Eilean Ni Chuilleanain in the eyes of Kinsella apparently didn’t conform to this tradition and doubtless nor would Dennis O’Driscoll, Matthew Sweeney, Maurice Riordan, Gerry Murphy or myself and many others. One might accept the argument that the senior list of excluded simply failed to make Kinsella’s grade on the criterion of basic poetic achievement were it not for the inclusion of Seamus Deane, Valentine Iremonger and a few other second-raters in their stead. I agree with Kinsella’s idea expressed over twenty years ago that things are never as coherent as they look. Generally in the Anglophone world poets have too much common sense to align themselves with one formal grouping or another. In an Irish context most if not all such perceived groupings are in fact journalistic entities, in so far as they are usually identified as such from outside the group and not bound by shared aesthetic or manifesto; but I also believe that Kinsella’s so-called dual tradition constitutes a grouping which would seek to deny entry to most Irish poets of the female gender and most Irish poets who happen to be men and who do not write within Kinsella’s atavistic tradition. In short I believe the poetry of Irish tradition and identity to be the greatest journalistic entity of all, one which encompasses the so called Northern Renaissance. In my wide reading of European poetry, my

acquaintance with critical monographs on the big names,

the listings of national anthologies, the word identity

doesn’t enter into matters. One might argue that Europe’s

poetries are more neatly contained within borders than

Irish poetry in English is. That would ignore the fact

that the two great German-speaking poets of the last

century were not German. Rilke was born in what is now the

Czech republic, educated at an Austrian military academy

and spent most of his writing life in Germany, France and

Switzerland. Celan was born in what is now the Ukraine,

published his first poems in Romanian periodicals, had his

first book published in Austria (selling less than thirty

copies in its first two years of publication by the way),

lived the rest of his life in France, published in Germany

but was shunned by the contemporary German group 47,

initially for the trivial reason that he read his poems

aloud in the Eastern shamanistic fashion, whereas the

Germans preferred a non-showy, non-emotive declarative

style of public reading. Yet national identity, how an Irish poet and his or her work might fit into tradition, might be shaped by Irish history is practically the only critical discourse that goes on in Irish studies departments, relieved occasionally by the attentions of gender ideologues. Both the nationalist (of green and orange varieties) and gender critical camps fall into the categorisation of “enemies of poetry” as explained by the great Trinity classicist W.B. Stanford in his book of that name. For Stanford, and a great many poets, the enemies of poetry include those scholars and critics who would treat poetry as if it were essentially a way of presenting information, history, science, education, ethics or politics. Rarely in an Irish context is a poet assessed on his or her use of diction; the basis of his or her aesthetic provenance or kinship. Where a poet’s relationship with language is examined it’s usually exclusively in relation to Irish, or where an academic has risen to the bait of a poet sprinkling his work with slang or dialect which forms no natural component of his own diction. In this case it’s always a man. Many poets, desperate for any kind of

attention whatsoever for their work are quietly complicit

in this great criminal undertaking. It’s one thing to be

complacent about how others read your work (and in the

real world one has no real control over such matters

anyhow) but it’s quite another thing to deliberately set

out to write poems which fall more easily within the

parameters of such critical discourse. And of course in

the context of writing primarily to generate academic

exegesis this is an appropriate moment to point out the

existence of a small pond, the anachronistic grouplet in

Irish poetry referred to variously as the modernists and

neomodernists who write texts in a post-modernist world,

specifically for one another and the handful of critics

who write about them. Thankfully we are in the dying moments of this historical phenomenon. Affluence at home has acted as an emigrational tourniquet. The steady stream of Irish blood fleeing across the Atlantic is coming to an end. The collapse of Irish-American political influence is signified by the exponential rise in Asian-studies and Latino-studies departments overtaking Irish Studies in popularity and sources of lucre.

And such an expectation was stupid long before the existence of the internet or the phenomenon of immigration in Ireland. In the 1960s Penguin began a stupendous series of modern poets in translation which revolutionised the way many poets working in English wrote. The revolution was most noticeable in America with the rise of poets such as Charles Simic, Stephen Dobyns, James Tate, and others. In Britain any such innovative tendencies were quashed at the xenophobic doors of newspaper reviewers and commissioning editors. Where the work of Zbigniew Herbert, Paul Celan or Miroslav Holub was lauded in the critical pages of cold-war British journals any British or Irish poet who dared to reveal these influences in his or her own work was dismissed as lazy and incompetent for not working within the well-made-poem tradition, such censure extended as far as that great critical mind Anthony Twaite who dismissed Ted Hughes’s Crow and Thom Gunn’s Moly as being technically incompetent. I might just digress here to make the point that a great many people believe there are many different ways to make a poem well and that the so-called well-made-poem is not always made well. An example would be Sean Dunne’s obsession in his first two books with metrical regularity to the point where arguably page after page hammers the anvil of the inner ear with a sonic monotony. Incidentally if anyone thinks I’m being malicious here, this is a criticism I made while Sean was still alive in a review which Sean thanked me for having written. I like to think that the greater musical variety of his third book resulted from an assimilation of this point. Thankfully the emergence of a generation of British poets born in the 60’s and nurtured on those very same Penguin modern poets in translation has dispelled all such reactionary poppycock, but not before seeing a poet like Dennis O’Driscoll remain critically ignored and taken for a lightweight throughout most of his career until recently, where most attention now is coming from non-Irish-Studies-specialist American peers. O’Driscoll might have been a highly influential voice in Irish poetry criticism were it not for his sensitive skin and the intimacy of the Irish poetry scene. After a scathing review O’Driscoll wrote of a James Simmons book, Simmons at a poetic gathering assaulted O’Driscoll in that marvellously gifted way Celts have with passive aggression by saying: “What did I ever do to you?” O’Driscoll later wrote, (with better manners than I have by not naming Simmons), “it never seemed to occur to him that I just didn’t like his poetry”. O’Driscoll stopped writing about Irish poetry from that moment on but continued to publish in journals such as the TLS, Poetry Review, Harvard Review, the Crane Bag, The London Review of Books and other places, articles which contained in their titles names such as John Berryman, Charles Simic, Stephen Dobyns, Tomas Transtromer, Kaplinski, Milosz, Symborska, Zagajewski and Holub. As with many other aspects of progress in Irish life there has been a delay of twenty years before developments in Britain, were mirrored here. The disintegration of reactionary hegemony in Irish poetry is only now beginning to gain momentum, There are a number of reasons why the Irish poetry publishing scene was so dysfunctional in the 80’s and 90s: most of the greater talents were published in Britain by Faber, Oxford, Cape, Anvil or Bloodaxe; few women were published. In a survey I conducted of poetry publishing in English in the Republic in late 1991 I could conclude that 89% of Raven Arts Press poets were male, as were 84% of The Gallery Press and 95% of Dedalus. Gallery had just one poet on its list who hadn’t graduated from university: Michael Hartnett. Very few of the poets published by Gallery were accepted without having been validated elsewhere first, either by having won a national prize or having been previously published by another publisher. Dedalus, which exercised more independent mindfulness in the judging of a new poet’s worth still published only graduates and practically only men. Essentially in 1991 if you were a new poet who happened to be a woman who had not entered university, had not yet won a poetry prize you stood the proverbial snowball’s chance of being published. The emphases on university graduates inevitably led to a situation where many of the most visible poets published were those who were also jobbing academics and more gifted and influential as academics than as poets and if you want me to name names Gerald Dawe and Seamus Deane spring immediately to mind. Like Dawe and Deane many of these poets who fitted the Irish Studies criteria perfectly were more than likely published by the Gallery Press, were devoid of any capacity for humour and mostly displayed ignorance of the innovations which had occurred to the free verse poetic line during the course of the 20th century. At this point I’d recommend a marvellous book just published by Graywolf Press, written by James Longenbach called “The Art of the Poetic Line”. Peter Fallon rightfully takes great pride in correctly claiming that most Irish poets submit their manuscripts to him before any other publisher, but I believe that he has drawn the wrong conclusions from this phenomenon. The Gallery Press has consistently published beautiful books for their time, involving quality paper, fine binding, tasteful typography, striking covers and excellent proofing. After the demise of Dolmen all other regular publishers on the Irish scene have been less consistent, verging often on the tacky in their production standards. Poets are generally bibliophiles and bibliophiles love the book as an objet d’art. Poets especially love their own books to possess the beauty of objets d’art and I have no embarrassment in proclaiming publicly that my own repeated failed attempts at getting published by Gallery had more to do with this issue than any faith in Peter Fallon’s editorial infallibility or anticipation of the company I might be keeping within the same catalogue. I digress at this point to say I have always found Peter Fallon to be an agreeable person whom I continue to admire for his commitment to his own ideals and the seriousness with which he has dedicated himself to the publishing of some Irish poetry, but only in the same way as I have great personal admiration for certain politicians whose parties I would never vote for. In the interests of Irish poetry I believe that the myth that Gallery Press represents all that is best in Irish poetry must be debunked.

So why Munster poetry? Why indeed? Am I merely proposing another apparently a priori journalistic entity? There would be some truth to that argument. On the level of Real Politik we are playing a game; the interests and commitments of young academics must be won over, they must be persuaded that the cultural produce of our own backyard is worth their attention. They must be persuaded that it is essential to be involved in an intellectual debate with ourselves. Academics generally work by comparing and contrasting. Before they can be persuaded that many of these poets can be worthy of individual assessment it would be easier to draw attention to their collective strengths. But the justifications for groupings of Munster poets are not just theoretical, I believe they can be derived from empirical observation. Heather Clark in her excellent introduction

to her book The Ulster Renaissance, Poetry in Belfast

1962 to 1972 addresses many of the questions

pertinent to identifying coherent groups of Munster poets.

She writes: “It is no accident that Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Southy were friends when they were young; if Pound, H.D., and William Carlos Williams had not known each other would they have become William Carlos Williams, H.D. and Pound? There have been lone wolves but not many. The history of poetry is a history of friendships and rivalries, not only with the dead great ones but with the living young.” Peter Sirr reacted to my call for papers on Munster poets with deep scepticism, a scepticism he has not applied to an alternative grouping proposed by Justin Quinn and David Wheatley which contains Sirr, the two young academics themselves and several other poet academics close in age. Wheatley qualifies this grouping by making the point:

Val Nolan has written an article reporting on a recent talk by John Montague at NUIG which will be published next month in Southword. Nolan writes: "He also believes youthful jealousies and anxieties to be ‘extremely healthy’ and poets should ‘continue to feel a sense of competition.’ Citing ‘Tom’ Kinsella as his example, Montague believes that good poets flourish only with ‘extraordinary peers’, what he calls the ‘how-did-they-do-that’ effect. ‘Look,’ he says, ‘at the “Ulster team”. They play as a team; the Arts Council sees them as a team… When this happens, ‘a generation begins to emerge that is different’." Aside from having sympathy for Montague here in his apparently unrequited relationship with Kinsella (if we are to remember Tom’s response to Haffenden) we can recognise how appropriately Montague’s “extraordinary peers” effect applies to that generation he is rightfully or wrongfully credited with spawning. Certainly his presence with Lucy in the English department of University College Cork during the 70s and early 80s facilitated an atmosphere where would-be poets were more than tolerated but actually encouraged. And many of these would-be poets escaped their conditional qualification. Poets who passed through UCC during this period with almost apostolic succession included Gregory O’Donoghue, Maurice Riordan, Theo Dorgan, William Wall, Gerry Murphy Thomas McCarthy, Sean Dunne, Greg Delanty and Liz O’Donoghue. All of these poets have to a lesser or greater extent been competitive, supportive peers who avidly read one another’s work and were spurred to improve individually by so doing. Other characteristics which these poets have in common is that with a couple of exceptions their work has been too cosmopolitan in character to have interested the Irish Studies specialists. They are all relatively laid back in style and tone which is not to say technically negligent. Even a syllabically coherent poet such as Thomas McCarthy is linked to the wildly enjambing Gerry Murphy by an avoidance of what August Kleinzahler has identified as the self-important Nobelese posturing language common in Heaney, Wallcott and Muldoon. This Cork grouping has had an above-average interest in translation and the production of versions; even before the Cork 2005 translation project came about, undoubtedly influenced by their deeper absorption of European and American poetry than pre-1990 British work. Aside from this group, the undeniable Innti group also emerged out of UCC at this time and in translation have influenced even those Cork poets without Irish. But the threads of kinship spread through Munster both geographically and generationally. The surreal is something which runs through the work of Gerry Murphy, Patrick Galvin and Paul Durcan, the latter having lived and worked in Cork for twenty years and who was included in Dunne’s 1985 anthology the Poets of Munster. Galvin, in turn has other connections, to the folktale worlds to be found in Hartnett and Ni Dhomhnaill. Hartnett in turn displays European influences which are also echoed in the work of Galvin, O’Grady, Wall and Riordan, and Asian influences echoed in Dunne. For the brave young academic, with a genuine interest in poetry, the opportunity to make a name through original, pioneering scholarship, avoiding the overmined Joyce, Beckett, Kavanagh, Yeats and now too the Ulster Renaissance, is presented by Munster poets. There are other areas, groupings of poets in Ireland, one as I said earlier identified by Wheatley and Quinn, who present research possibilities, but wearing my hat as Artistic Director of the Munster Literature Centre I’ll leave it up to others to plead their case.

|

||

|

|

|

|